The Confederate high command in Richmond desperately sought a suitable replacement for Breckinridge in the Department of Western Virginia. The ranking officer in that department, Brigadier General William E. “Grumble” Jones, remained uncertain of his position. On May 20, at his headquarters near Abingdon, Virginia, Jones received a telegram from General Samuel Cooper ordering the retention of Brigadier General John C. Vaughn’s Tennessee cavalry brigade in the Department. The tone of the order implied Jones to be the acting commander of the Department, but failed to enumerate. Perplexed, Jones telegraphed General Cooper in Richmond, “Must I assume command of the Department of Western Virginia?”[i] No response came, so on May 23, Jones again telegraphed Cooper:

No order has reached me merging the Department of East Tennessee and Western Virginia, though telegrams have reached me which would imply such had been done. I was directed by General Bragg to watch the enemy coming from Kanawha, and in cooperating with General Jenkins I found myself in the Department of Western Virginia. Now my command is in both departments, and I will continue to command both until further orders, or the arrival of a superior officer.

Cooper responded by issuing an order for Jones to assume command of the Department of Western Virginia. With his old army appetite for direct orders quenched Jones set about to fulfill his duties.[ii]

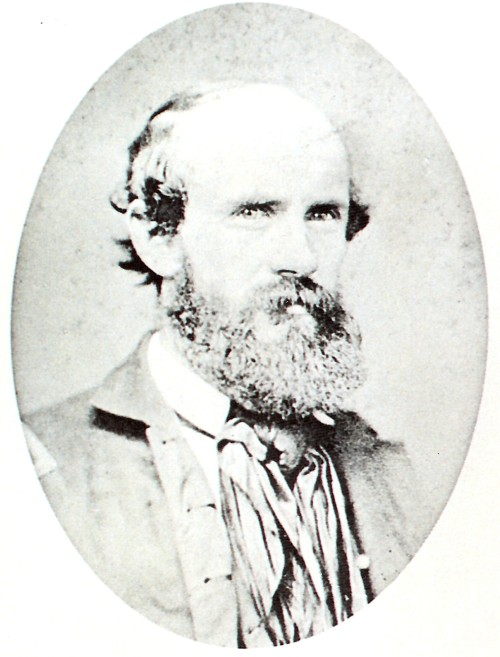

Born on the middle fork of the Holston River on May 9, 1824, William Edmondson Jones grew to manhood in Washington County, Virginia, near the Tennessee border. During the American Revolution, his Edmondson forebears had been “Overmountain” men who turned the tide of that conflict at the battle of King’s Mountain in 1780. Jones grew up learning the tough ways that allowed the Appalachian pioneers. At the same time, he received an extensive education at Emory and Henry College before attending West Point. He graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1848, ranked twelfth out of forty-eight cadets. After spending three years in Oregon as a Lieutenant, the young officer returned home to marry Miss Eliza Dunn. On the return trip, the young couple sailed from New Orleans. A violent storm wrecked the ship which carried them. When they attempted to land in a lifeboat, a wave swept Eliza from the small vessell. Only the heroism of Thomas B. Edmondson, the Lieutenant’s cousin, saved him from the same fate. The whirling waters washed away William’s dreams and hopes of a long and happy life together. Eliza’s body was recovered and buried at Glade Spring Presbyterian Church back in Virginia. Stunned by his tragic loss, Jones returned to his post with a heavy heart. The young widower immersed himself in his duty in order to avoid the pain of his loss and became “embittered, complaining and suspicious.” He eventually became known as “Old Grumble Jones” and could be “a disagreeable customer when crossed.” It is likely, however, that some of these qualities existed even before Eliza’s death given the rugged background of the Jones’ family. Finally, in September 1856, he resigned from the army and returned to his estate on the Holston River. In 1857, Jones visited Europe on military business for the state of Virginia.[iii]

Politically, Jones believed in Southern society and in the rights of the individual states. He saw slavery as an economic necessity beneficial to both master and slave. When John Brown raided Harper’s Ferry in an attempt to stimulate a slave insurrection in 1859, Jones urged Virginians to revitalize and reorganize the Commonwealth’s ability to defend itself through a military means. “It is as much our duty to prepare for the coming dangers,” declared Jones, “as to defend our assailed rights and none but the obstinate blind can fail to see the dangers great and most horrible in our future.”[iv]

When the war broke out in 1861, Jones raised a company of cavalry from Washington County known as the Washington Mounted Rifles, and became its first captain. The company joined Colonel James E. B. “Jeb” Stuart’s 1st Virginia Cavalry Regiment, and took part in the First Battle of Manassas under Jones’ able guidance. He ultimately rose to the rank of colonel, but in April of 1862, Jones fell out of favor with Stuart, and the regiment voted him out of office due to his harsh disciplinary practices and embittered attitude. With competent officers in short supply, Jones received an appointment as the colonel of the 7th Virginia Cavalry in July 1862, replacing the the fallen Turner Asby. Jones instilled discipline in Ashby’s rowdy horseman and displayed aggressive the aggressive streak that Stonewall Jackson admired. In early August, Jones encountered and attacked a vastly superior force at Orange Court House. “No time could be afforded for inquiries-to fight or run were the only alternatives; I chose the former…”[v]

By September, Confederate authorities promoted him to brigadier general at the request of Stonewall Jackson. The latter had Jones placed in command of the Valley District but his personality and military ways elicted complaints from local civilian leaders. In May 1863, the crotchety Virginian led his brigade on a raid into Union held West Virginia in a joint mission with Imboden. This highly successful raid destroyed sixteen railroad bridges and two trains, seized 1,000 head of cattle and 1,200 horses, and captured seven hundred prisoners. Additionally, Jones ravaged the oil works at Burning Springs, destroying 3,000 barrels of oil and all production facilities. Robert E. Lee complimented General Jones on the raid’s sagacity and boldness.

Upon returning to Virginia, Jones and his brigade rejoined Stuart’s cavalry with the Army of Northern Virginia near Culpepper Courthouse. On June 9, his vigilance at Brandy Station while Stuart conducted a dress parade saved the cavalry from defeat. Jones’ command withstood repeated Union assaults and played a decisive role in preventing disaster there. However, His icey relations with Stuart continued. When Jones warned Stuart of approaching Union troopers, the Cavalry chief replied, “Tell General Jones to attend to the Federals in his front, and I’ll watch the flanks.” When Jones received the reply, he snarled, “So he thinks they ain’t coming, does he? Well, let him alone, he’ll damned soon see for himself.”[vi]

Jones attempted to resign from the service instead of serving under Stuart, but General Lee withheld the resignation. Nevertheless, Jones continued his consistently dependable efforts throughout the Gettysburg Campaign. Although Stuart purposely assigned the capable Jones’ rear echelon duty, he effectively led his brigade in several combats throughout the campaign, including actions at Upperville and Fairfield. His command twice crossed swords with the 6th U.S. Cavalry during the campaign. After inflicting 242 casualties upon that regiment and defeating it on two separate occasions, Jones reported, wryly “The Sixth U.S. Cavalry numbers among the things that were.”[vii]

Finally, Jones’ feud with Stuart boiled over as Lee’s army returned from Gettysburg. Jones took exception with something Stuart did and wrote his commander “a very disrespectful letter.” In spite of their differences, Stuart had considered Jones “the best outpost officer” in the Army of Northern Virginia. Stuart recognized that Jones’ “watchfulness over his pickets and his skill and energy in obtaining information were worthy of all praise.” Stuart’s praises for Jones were matched only by his desire to have him removed from his command. When he received Jones’ letter, Stuart promptly relieved Jones of his command and placed in “close arrest.” This incident resulted in a court martial and ended Jones’ service with the Army of Northern Virginia.[viii]

In the aftermath of the court martial General Lee wrote Confederate President Jefferson C. Davis:

I consider Jones a brave and intelligent officer, but his feelings have become so opposed to General Stuart that I have lost all hope of his being useful in the cavalry here… he says he will no longer serve under Stuart and I do not think it would be advantageous for him to do so, but I wish to make him useful.[ix]

As a result of Lee’s recommendation, the Confederate War Department assigned Jones to the Department of Western Virginia. There he received command of a brigade of undisciplined Virginia cavalry regiments. Jones instilled these men with discipline and drastically improved their performance on the battlefield. In November, Jones routed a Union force at Rogersville, Tennessee, capturing 700 prisoners with their wagons and equipment. On January 2, 1864, Jones captured 385 men and three pieces of artillery by surrounding a Federal force at Jonesville, Virginia. During February, his troopers defeated the 11th Tennessee (U. S.) Cavalry at Wyerman’s Mill and apprehended 265 Union soldiers, eight wagons and one hundred horses. The Richmond Whig declared General Jones to be the “Stonewall Jackson of East Tennessee.” In early May, Jones combined with General John H. Morgan in the successful defense of Wytheville and Saltville against General William W. Averell’s blue coats.[x]

Jones’ experience as a cavalry commander justified his assignment to command the Department of Western Virginia. His reputation had been built upon the utmost vigilance and the ability to use scouts and patrols to obtain accurate information on enemy movements. When “Old Grumble Jones” learned where the enemy was, he did not allow them to sieze the initiative. Instead, Jones aggressively went on the offensive and hoped to catch his opponents with their guard down. From Orange Courthouse to Wyerman’s Mill, Jones had done just that. Most of the time, his efforts were rewarded with success and outright failure was unkown. In the Shenandoah Valley, Jones would be called upon to put his ability to the ultimate test. No longer would he be leading a brigade or two of cavalry. Now he would lead a combined force of all arms against rejuvenated opponent intent on victory.

[i] OR, 37:pt.1:745.

[ii] OR, 37:pt.1:746-747.

[iii] Thomas W. Colley, “Brigadier General William E. Jones,” Confederate Veteran, 6:266-267; Personal Reminiscences of a Maryland Soldier in the War Between the States 1861-1865., 81.

[iv] William E. Jones Papers, Library of Virginia.

[v]OR, 12:2:112.

[vi] Thomas A. Lewis, The Civil War: Gettysburg, Confederate High Tide. Time-Life Books, 1985, 20.

[vii] OR, 27:2:754.

[viii] Warner, Generals in Grey., pp. 166-167; Colley, CV 6:266-267; Andy Maslowski, “Burning Springs, Va.,” America’s Civil War, Sept. 1988, pp. 8, 65-66.

[ix] OR, 29:2:771-772.

[x] Colley, p. 267; Warner, p. 166-167; Jeffrey C. Weaver, 64th Virginia Infantry. (Lynchburg: H. E. Howard, Inc., 1992), p. 86.

For more on the Battle of Piedmont