Welcome to my blog on the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign. My name is Scott Patchan and I have studied this topic in intricate detail for nearly twenty-five years. Over the course of that time, I have written three books on the topic, The Forgotten Fury: The Battle of Piedmont; Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign; and Opequon Creek: The Last Battle of Winchester. I also served as an historical consultant for Time-Life’s Voices of the Civil War: Shenandoah 1864 and have written dozens of articles and led dozens of tours on Valley Topics, not to mention my scores of visits to Valley battlefields. I have served on the Kernstown Battlefield Association Board of Directors for nearly ten years now.

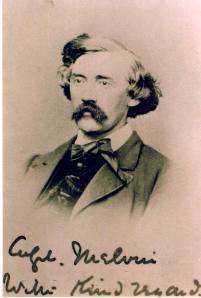

My purpose in writing this blog is to move beyond the bounds of traditional publications and share aspects of my research with fellow Civil War enthusiasts that might not otherwise see the light of day. Having met so many good friends over the years in the course of my research, I hope to make many more through this blog. With my inaugural post coming on Saint Patrick’s Day, I thought it appropriate to delve briefly into the life of Colonel James A. Mulligan who gave his life for the Union Blue on the green fields of Kernstown on July 24, 1864.

Mulligan was born to Irish parents in Utica, New York on June 25, 1830, but the family moved to budding frontier town of Chicago, Illinois in 1836. His father died while he was still young but his mother subsequently married a successful Irish farmer

whose largess later allowed Mulligan to attend college. Of his youth in Chicago, Mulligan looked back fondly upon his “halcyon days when we hunted pigeons and hoed corn, [and] sparked the girls in mellow sunshine.” Mulligan also grew up to be a devout and practicing Roman Catholic, graduating from the University of Saint Mary’s of the Lake in 1850, quite an accomplishment for the son of immigrants in those days.

After graduation he studied law in Chicago, but yearned for adventure. He found it in 1851 when he joined an expedition that was surveying the path for a railroad across the Isthmus of Panama, serving as clerk for the project. When he returned home in 1852, he resumed his legal studies. In 1855, he became the editor of The Western Tablet, a Catholic newspaper published out of Chicago. The following year, Mulligan gained admission to the Illinois Bar and began practicing long. He soon became a rising star on Chicago’s Democratic political scene, becoming associated with the powerful Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Mulligan moved to Washington and spent a year clerking at the Department of the Interior but determined he had had “enough” of Washington and went home to Illinois.

In 1857, Mulligan met the beautiful Marian Nugent and made her his “Darling Wife” after two year courtship. In 1860, Mulligan used his powerful oratorical skills to campaign for Douglas in the presidential election. When the Southern States began to secede from the Union upon Lincoln’s election, Mulligan wrote, “ Dare now to preserve this government, vindicate its strength and the republic passed through this crisis will stand with such assured dignity and firmness through all the coming centuries, that no foe without, no Judas within shall ever dare raise an armed hand against her.” He then used his powerful personae to raise “Mulligan’s Irish Brigade” from Northern Illinois with one company of Detroit Irish thrown in for good measure.

The unit subsequently was designated the 23rd Illinois Volunteer Infantry and saw its first action at the Siege of Lexington, Missouri in September of 1861. When the firing briefly ceased, Confederate General Sterling Price sent note asking Mulligan why the firing stopped. Although vastly outnumbered, Mulligan coyly replied, “General, I hardly know unless you have surrendered.” Although Mulligan ultimately surrendered his outgunned forces, he became a symbol of hope against long odds at a time the north had endured shameful defeats at Bull Run in Virginia and Wilson’s Creek in Missouri.

After being exchanged, Mulligan and his men spent the next two years guarding the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in West Virginia. Although he longed to join the Army of the Potomac’s famed Irish Brigade, it was not to be. Nevertheless, in the spring of 1864, Mulligan and his men signed up for another tour of duty when their enlistments expired, lured no doubt by the opportunity for a thirty-day furlough home.

Mulligan returned to action in time to resist the General Jubal Early’s Confederate raid on Washington, D.C. and assist in the pursuit back to the Virginia. On July 24, 1864, Mulligan led his command at the Second Battle of Kernstown. Although he warned his commander, General George Crook, that the Confederate army was in full force, Mulligan received orders to attack. Mulligan questioned the orders through a staff officer but was told in no uncertain terms to advance immediately. He complied and the results were disastrous. Mulligan rallied his Irish Brigade and 10th West Virginia infantry behind a fence lining a lane on the Pritchard Farm. As he rode behind his battle line urging the men to stand firm, a Rebel bullet struck his leg. His men lowered him from his horse but he was struck in the torso by two more bullets before they placed him on the ground. His 19-year old brother in law, Lieutenant James Nugent came to his aid only to be shot and killed instantly. Mulligan’s men refused to leave him so he ordered them to “Lay me down and save the flag.” He died in the Pritchard House two days later.

His pregnant wife Marian left their two young children with a Unionist family in Cumberland, Maryland and rushed to Winchester but by the time she arrived he had already died. Thousands of people awaited the arrival of Mulligan’s remains at the Chicago Rail Station and even more attended his wake and funeral.

For all of Mulligan’s popularity while he was alive, he quickly vanished from the pages of history. Yet his devotion to God, Family and Country like that of so many who have given their lives for American liberty lives on to this day in the daily lives of millions of Americans as they go about their daily lives.

For further reading see:

Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign by Scott C. Patchan