Thursday, August 29, 2013

The 1864 battle of Winchester in Virginia marked a seminal point in the War of Rebellion and became a proving ground for United States Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s field leadership.

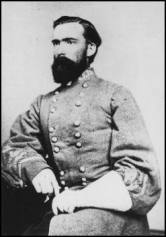

Leading the enemy army was Jubal A. Early, former prosecuting attorney and General Assembly delegate from Franklin County who also argued in the General Assembly against secession (as his constituents wanted).

Shenandoah Valley native and Civil War historian Scott Patchan offers a fresh account of that battle in his new book, “The Last Battle of Winchester.”

Most of the book is filled with descriptions of troop movements and battles. You would expect that. What you might not expect is vibrant prose and clear descriptions that are engaging in a way not usually found in books about warfare.

Patchan tells about the troop movements as if he were a journalist witnessing the action. There is nothing dry or academic in this narrative. It will transport you to the lower Shenandoah Valley in 1864.

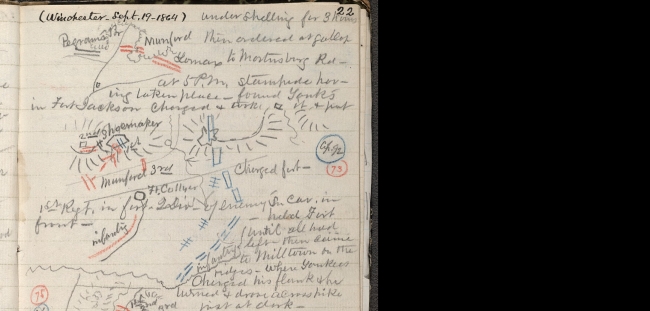

And there are maps . No book about battlefields and the movement of two armies and their many divisions should be without maps — lots of maps.

Another distinction of Patchan’s book is his use of the prose style of the Cult of the Civil War.

Sheridan is often referred to as “the Ohioan ” or “Little Phil” or the “little Irishman from Somerset, Ohio.” George Armstrong Custer is sometimes called the “blond cavalry officer.” And Confederate soldiers are called “butternuts,” a reference to the color of their uniforms.

The use of sobriquets is common among Civil War enthusiasts. It shows a level of familiarity and camaraderie that one soldier feels for another. It establishes “street cred” among the true believers, and it provides a kind of charm distinctive to the genre. The use of contemporaneous slang also enhances the descriptive power of the author by re-creating the atmosphere of the time.

If there is a fault in the book, it is the Monday-morning quarterbacking that also is a characteristic of people who study war. After any battle, everybody is a better general than the man in the field — especially if the battle is almost 150 years old.

To deflect some of Patchan’s criticism of Sheridan, consider this defense: Sheridan was developing a new means of using the disparate units of his army as a solidified force, not as separate units fighting in the field, but as a cohesive fighting force. This new use of an army was pioneered by Sheridan during the campaign from Winchester in 1864 until Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender in April 1865.

The “missed opportunities” for complete defeat and the resulting prolonged war also appears to be part of the overall philosophy of utter and total defeat which would discourage soldiers and citizens from trying to restart the war.

As Sheridan said to Prussia’s Otto von Bismark in 1870, “the people must be left nothing but their eyes to weep with after the war.” One way to accomplish that is to drive an army to the point that it begs for the opportunity to surrender.

What matters with “The Last Battle of Winchester” is that this book is an excellent account of the facts of the battle. It evokes emotions associated with the warfare. At times, Patchan’s descriptions of battle will make your heart race as if you were in the field yourself. The plentiful graphics help you keep your bearings.

One strong benefit for local readers is the depiction of Early, especially when Patchan exposes his sense of humor. One such incident involved Maj. Gen. John Breckinridge — a Kentuckian — who, having heard many references to first families of Virginia, asked what happened to the state’s “second families.”

Early overheard the questions and offered an answer : “They all moved to Kentucky.”

Patchan always finds time to clearly explain the overall strategies of both sides of the conflict as each tried for decisive victories in the field while protecting their respective capital cities and their valuable railways. Strategy for the United States included a need for significant victory in the Shenandoah Valley in order to support efforts to re-elect President Abraham Lincoln.

Read this book. If you are a Civil War buff, the battlefield action will excite you. If you are interested in history, knowing more about a campaign that helped the survival of the United States will enlighten you. If you are neither, the prose will delight you. If you travel through the Shenandoah Valley, the vivid description of the scenery and what happened there 150 years ago will ignite your imagination so you will have a new appreciation for ground over which you travel.

Maj. Gen. William H. Emory, “Old Brick Top,” as he was known in the Regular Army or more simply the “Old Man” to the young soldiers who served under him, is generally viewed as the weak link in the command structure of Gen. Phil Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah. He was certainly an outsider; General Horatio Wright commanded the Sixth Corps from the Army of the Potomac and had fought through Grant’s bloody Overland Campaign. General George Crook was Sheridan’s West Point roommate and a fellow Ohioan. Sheridan’s chief of cavalry, Gen. Alfred T. A. Torbert had served his commander as a division commander since May of 1864. All three of these men had, to one degree or another, already established a relationship with Sheridan, their commander. At fifty three years of age, Emory was also significantly older than the other officers, including Sheridan who was only 32. Emory developed a reputation as a worrier throughout the war. During the Port Hudson, Louisiana Campaign of 1863, staff officer David Hunter Strother believed that Emory’s timid councils were having a negative impact on Union commander Nathaniel Banks. When the fighting at the Third Battle of Winchester or Opequon Creek, temporarily went against the Union, Emory believed that all was lost, but in the end the Union forces achieved victory.

Maj. Gen. William H. Emory, “Old Brick Top,” as he was known in the Regular Army or more simply the “Old Man” to the young soldiers who served under him, is generally viewed as the weak link in the command structure of Gen. Phil Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah. He was certainly an outsider; General Horatio Wright commanded the Sixth Corps from the Army of the Potomac and had fought through Grant’s bloody Overland Campaign. General George Crook was Sheridan’s West Point roommate and a fellow Ohioan. Sheridan’s chief of cavalry, Gen. Alfred T. A. Torbert had served his commander as a division commander since May of 1864. All three of these men had, to one degree or another, already established a relationship with Sheridan, their commander. At fifty three years of age, Emory was also significantly older than the other officers, including Sheridan who was only 32. Emory developed a reputation as a worrier throughout the war. During the Port Hudson, Louisiana Campaign of 1863, staff officer David Hunter Strother believed that Emory’s timid councils were having a negative impact on Union commander Nathaniel Banks. When the fighting at the Third Battle of Winchester or Opequon Creek, temporarily went against the Union, Emory believed that all was lost, but in the end the Union forces achieved victory.